News April 2020

Raising concerns over plans for Philharmonic’s “reimagining” of David Geffen Hall

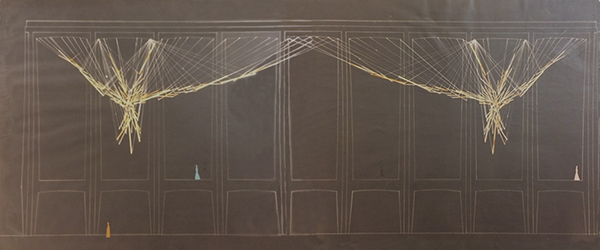

In December 2019, New York Philharmonic and Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts publicly announced “Working in Concert,” a joint project for the “reimagination of David Geffen Hall.” The performance venue, known as Avery Fisher Hall for most of its 58 years, was designed by Max Abramovitz (1908–2004) and completed in 1962 as one of the original trio of Lincoln Center buildings fronting the plaza. The first thing that registered with many fans of the symphony’s hall upon seeing the plan was that the “Lippold” was not coming back. The Lippold being Orpheus and Apollo, the five-ton site-specific sculpture of gold toned Muntz metal bars suspended on 450 thread-like wires within the hall’s four-story, Grand Promenade atrium. Commissioned by Abramovitz and created by Richard Lippold (1915–2002) as an integral part of the hall’s original design, Lincoln Center announced in 2014 that the celebrated work was being “removed temporarily for maintenance and conservation.”

Over the past 15 years several plans for reimagining the Philharmonic’s house have been launched and abandoned, one headlining Sir Norman Foster as architect and a more recent, Thomas Heatherwick. The hall is no stranger to overhaul. The auditorium interior was gutted and rebuilt in the early 1970s to remedy poor acoustics plaguing the original design. Since the December announcement, there has been zero resistance to another full gutting and redesign of the auditorium. The plans released for the reimagined auditorium—by Diamond Schmitt Architects, working with Akustiks and Fisher Dachs Associates—are an exciting rethinking of the audience experience well beyond acoustics and the technical needs of today’s performers.

The missing Lippold on the other hand signaled an aggressive reconfiguring of the signature atrium, one that would substantially alter Geffen Hall’s presence on the plaza and its relationship to the opera house and NY State Theater—together monumental houses that define the performing arts center. Design of the public spaces, separate from the auditorium, is in the hands of Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects/Partners. DOCOMOMO US/New York Tri-State’s position is that the following aspects of the proposed public spaces redesign eliminate or substantially alter defining elements of the original design and are therefore inappropriate and should be reconsidered:

• The four-story atrium rising from the promenade level will be reduced to three. The upper story volume will be brought out to the exterior envelope presenting as opaque rather than transparent from the exterior. The space created will be used for offices and to conceal structural armatures for event rigging being introduced to enhance the promenade’s function as an event rental space. From the exterior, the opaque top floor will be lit with a blue glow on the full perimeter.

• Small balconies called “promontories” will be introduced into what is currently atrium, breaking up the existing volume and compromising the original box-within-glass-box design. The balconies will be located at the east and west ends of atrium at the first tier level.

• A large digital “media wall” will be added in the ground level foyer facing Josie Robertson Plaza.

• Permanent removal of Richard Lippold’s suspended sculpture Orpheus and Apollo.

The proposed changes to the primary façade disregard the significance of the shared design principles responsible for the “look inside” atriums that unite and animate the three-building ensemble that defines Lincoln Center around the world. Each atrium was designed with full-façade transparency, depth and a clear articulation of the auditorium tiers and function within. Whether it’s Orpheus and Apollo, the Met’s Chagalls, Philip Johnson’s prismatic pop art fixtures or a bustling audience during intermission, a view from the plaza is integral to the art and performance that is Lincoln Center. In its press FAQ information New York Philharmonic and Lincoln Center state “The iconic exterior of the hall will not be modified.” This is a duplicitous evasion of the fact that if you change what’s directly behind a transparent façade, you have changed the façade.

On January 27 representatives from DOCOMOMO US/New York Tri-State attended a meeting organized by Landmark West! at which members of the project team—owners and architects—shared details of the project, answered questions and heard initial feedback from preservation advocates. A follow up meeting with project architects scheduled by DOCOMOMO US and DOCOMOMO US/New York Tri-State for mid-March was called off due to growing Corona virus concerns but will be reinitiated. It should be noted that no part of Lincoln Center holds NYC landmark protection. Request For Evaluation (RFE) forms have been submitted to the LPC in the past by DOCOMOMO US/New York Tri-State and others. The commission has not acted, presumably because Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts has expressed over the years that it does not want the site or individual buildings landmarked. In 2000, following an exhaustive nomination application led by Landmark West!, Lincoln Center was determined eligible for the State and National Registers of Historic Places. It was never added to the Registers because Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, as owner, declined to provide the required owner consent. In February 2020 the Preservation League added Orpheus and Apollo to its 2020–2021 “Seven to Save” List.

The three main houses were designed to work as a whole on Philip Johnson’s Piazza del Campidoglio inspired plaza. The way they open up to the plaza at night, luminous and transparent, is one of few features critics have collectively applauded since the Center’s debut. Anyone who has walked up onto the plaza at night during intermission has surely experienced the elegance and magic of it all. Justin Davidson, in his announcement of the “reimagination” project for New York magazine called Geffen Hall an “eggshell-and-gold lightbox.” That’s nailing it. Note: Lincoln Center has never shied away from gold or gold like. (Isn’t that part of why we love it?)

The design commonalities most responsible for this overall experience didn’t just happen because the architects liked design by committee. Over the course of 1958, architects were confirmed for Lincoln Center’s six buildings: Wallace Harrison, Max Abramovitz, Philip Johnson, Eero Saarinen, Gordon Bunshaft and Pietro Belluschi. They became the “architects panel” and met throughout 1958 and early 1959. John D. Rockefeller 3rd, president of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Inc., had direct responsibility over the panel. He hired Rene d’Harnoncourt, director of MoMA at the time, to be advisor and liaison between the architects panel and the Board of LCPA, Inc. By August 1959 the panel had agreed on its “unifying elements”: the travertine, matching promenade/balcony height, similar massing for the symphony hall and state theater. They even agreed that Harrison’s opera house could be more sculptural, more grand. Abramovitz’s symphony hall, now Geffen Hall, was designed and completed first, so it is quite likely that as a test case for the shared design principles it had more impact on the other buildings than vice versa.

More than simply the loss of the Lippold, concerns should be raising about the future of Lincoln Center architecturally, and writ large. Looking back on the project d’Harnoncourt commented that without the unifying elements the Center would have had a “world’s fair atmosphere.” Our role as preservationists—or simply New Yorkers who have come to love Lincoln Center’s architecture—is to prevent a heedless takeoff down that slippery slope.

New York Philharmonic/Lincoln Center project site “Working in Concert”

LandmarkWest! site with excellent background on Richard Lippold’s Orpheus and Apollo and David Geffen Hall